A Mirror-Like Lacquer Coating |Lacquer Master

- himejifestival

- 2022年3月3日

- 読了時間: 7分

更新日:2022年3月5日

Hello! I run a group whose goal is to communicate the charms our city has to offer by promoting the annual fall festivals that are held throughout the region. The festivals have now been abandoned for two years in a row, with both the 2020 and 2021 events cancelled due to COVID-19. Fortunately, this has given me the opportunity to interview some local artisans in their home studios. Banshu's fall festivals are known for their “yatai”, a traditional parade float combined with a palanquin. The yatai here are decorated in a much more extravagant way than those of other areas. I have seen these floats countless times since I was young, and to be honest, I used to take them for granted, but now I would like to take a moment to highlight the workers behind the crafts that are such an important part of our festival. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Lacquer Master

Takashi Sunagawa - Head of Sunagawa Lacquer Crafts

Born in 1973 in Himeji, Takashi is the fourth-generation head of Sunagawa Buddhist Altars, and first-generation head of Sunagawa Lacquer Crafts. They continue to do lacquering, gold leaf stamping, and coloring as their main business, even as they also engage in the manufacturing, selling, and repairing of Buddhist altars, as well as doing the lacquering on the various floats used in Nada’s famous Kenka Matsuri (Fighting Festival). In 2016, they received the Hyogo Prefecture Craftsmanship Achievement Award.

The roofs of Banshu’s yatai are covered with a pitch-black lacquer. I always wondered how they can make such perfectly black and beautiful roofs!

Q: Our interview team was born in Himeji, so to us, a yatai with a lacquered roof is normal. But, I was surprised to find out it is not done this way everywhere in Japan. Have you heard this?

A: Yes. My understanding is that it is unique to Banshu. In other regions, at a Danjiri festival for example, they would mostly use unpainted wood. Himeji is a castle town. So, it is likely related to the fact that in samurai society, many people used lacquer. It is because it was a very wealthy area.

We have the mountains as well as the sea, so there is an abundance of food. Since ancient times, places like these have been important geographically in industrial development.

The yatai were made from what the people of the village could provide. The elements of carving, decorating, sewing, and painting are all combined. That is what is amazing. In Banshu, we renew these works every 15 years or so. For festivals in other areas, the yatai usually are not refurbished so soon as they tend to last longer. And as I am sure you're aware, there's also the spirit behind it all.

Q: Well, Banshu festivals are intense. And lacquer gives off an expensive image. So, on a yatai, it’s really something else!

A: It looks quite expensive, right? (laugh). I only use all-natural lacquer in my work. The character for "lacquer" in Japanese is also used in the word for "jet-black," so black lacquer really is the embodiment of the ideal. It is also a color that reacts with iron. Natural lacquer is quite valuable, right now, one kilogram is actually worth about ¥150,000.

Q: It takes a lot of time and work, doesn't it?

A: Well, lacquer is obtained from trees. Cuts are made into a tree, and then the lacquer seeps out where it is harvested by a collector. One tree usually provides about 180ml. In one day, a collector can harvest about 200ml of lacquer.

(The lacquer's color changes the longer it is exposed to air.)

Q: Just thinking about it feels daunting.

A: Actually, the tools are also quite expensive. The brush, well, it's made from real human hair.

Q: What?! Are you serious?!

A: Yes. Also, the hair must be untreated, and not dyed. The length also needs to be just right, so it can be quite difficult to obtain usable hair. Currently in Japan there are only around two people who make these brushes. One brush can cost, well, about ¥150,000.

Q: Seriously?! So, what can you tell me about the process of lacquering?

A: Okay, let’s say a village wants a new yatai made. For about two years they will hold festivals with yatai that use bare wood.

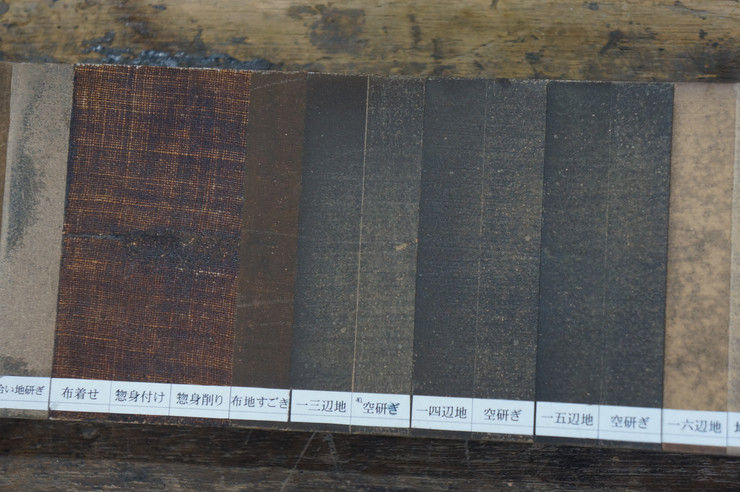

Then, after the two years pass, lacquer will be applied. My job starts here. Basically, I make the foundation and then apply the overcoat. Then more foundation, clean it up, foundation, clean it up, over and over… That goes on for about twenty-five layers or so. Finally, the topcoat is applied… Actually, from among the more than seventy steps in the process, 80% of them are the “foundation.” (laughs)

The foundation is absolutely the most important part. After the inside roof has been reinforced, first the seams of the top roofing board are reinforced with a kneaded mixture of lacquer, sawdust, and a rice glue called "kokuso". While that is hardening, we perform wood compaction by coating the entire roof in raw lacquer, which is then allowed to soak into the wood.

For the base layer, "kataji," a mixture of lacquer and zinoko (diatomite powder), is layered on several times. There are layers of linen cloth, kataji, and hemp cloth. And these layers are repeated. After twenty layers, a whetstone is used to gently smooth it out. When the surface begins to look good and has been adequately strengthened, the topcoat is finally applied.

To compare it to an animal, the wood is the bone, the foundation is the muscle, and the topcoat is the skin. Another way of saying it is that I read the lines envisioned by the carpenter, bring out a silhouette with the foundation, and make it shine with the coating.

The lacquer is applied three times. At each stage it is polished down before the next coat is added.

Q: So, you polish it down, rather than applying it in thin layers like paint?

A: Correct. After I apply the lacquer in as thick a coat as possible, making sure to prevent it from dripping, we polish it. I use charcoal to do that. Here, touch this sample to get an idea of what it feels like. (It’s really coarse!) The charcoal has been prepared to match the curves of the roof so it can be smoothed properly. Once this process is complete, the final stage is to apply a wax polish.

The wax polish is required to give the surface a mirror-like smoothness and glossy luster. Colza oil and deer antlers are crushed and baked together to create horn meal. This is used to polish the lacquer by hand, so that when complete, it really does look like a mirror.

Q: It is beautiful, but the process seems incredibly daunting. Lacquer has an expensive image, and the process seems to match. It’s incredibly...precious! (laughs)

So, my question is this. You do all this work to create a beautiful, mirror-like roof, and deliver it to the village. And in Banshu, the yatai are really put to work. They even get banged around sometimes! But look how beautiful it is! Do you ever think, "What a waste!" "It's going to get scratched!" Or anything like that? (I sure do! I have mixed feelings about it all.)

A: Haha! I guess you could compare it to F1 racing. Yatai are like F1 cars and Buddhist altars are like normal cars. An altar's base is about four layers, but a float has dozens of them. Why? The float gets used in direct sunlight. It gets rained on. It gets dropped on the ground or knocked into things, so, we have taken measures to prevent this sort of defect from showing up. In F1 there are also harsh conditions. If you do not do well, you might wreck the car, but, I feel like you still want it to be in the best shape possible. I’m proud to deliver the very best work to the very best festivals.

From the Participants

• Hiroko, a festival lover

I really love the shine of the lacquer. The process goes beyond what I could have imagined. The way the curves of the roof are done... It's like the lacquer artist brings the carpenter's imagination to life. Learning how much effort goes into obtaining the natural lacquer gave me such appreciation for all the tools.

This is the first time I’ve seen natural lacquer. The way it changes colors makes it feel alive. But, I especially love the way the polishing was done at the end.

At the shop, heard Mr. Sunagawa say "The yatai are not some kind of gallery piece." He meant that although they are traditional crafts, but they’re meant to be used not just appreciated, and that is what makes them so superb! Banshu is awesome! Himeji Yatai are awesome! I remember him saying that.

The materials disappear… The creators might all die off… There could be many terrible problems in the future… But, I just love how amazing it is that these things are made, not by machine but by the hands of true artisans. I adored the Himeji yatai before, but this just made me fall in love with them even more!

• Riku, an aspiring artisan (14 years old student)

I am so moved… I can barely put my feelings into words. All I've been able to say is "Wow! This is amazing!" So many things surprised me, like the original color of the lacquer and how many times it was applied. And hearing about both the skill of the craftsmen, and how expensive their tools are, really made me want to become part of this culture.

• An Exchange Student from China Studying the Banshu Fall Festival

I sensed that Mr. Sunagawa has immense pride in his work. I feel like he really conveyed what makes the festival so great, even to someone like me, an exchange student who was already interested in the festival. I believe the pride in local culture and these skills are the most important support the festival can have.

I learned about the Banshu Fall Festival after I was inspired by the Nada Kenka Matsuri (Fighting Festival). It is famous enough to be considered representative of the Banshu area and its history ranges from being a government event to a privately run festival. You can really feel the energy radiating from the people. But, since it encompasses the history of seven different villages, it does lack some of the intimacy it used to have, although I am still impressed by how people come together to keep the festival going.

コメント